Last Sunday's readings were about Jesus raising Lazarus from the dead, and Ezekiel's vision of The Valley of Dry Bones. The gospel tale is familiar to most folks even if they've never set foot in a church, but the Hebrew scriptural tale is known to many of us thanks to the tune of an old spiritual:

(Rain Man is a good movie, I think, but it's an even better soundtrack, and that song is one of the reasons.)

It's fascinating to read what scholars and interpreters have wrung out of these millennia old tales, and they can often provide a context difficult to conjure for most of us 21st century types. For many of us, the idea of a valley filled with skeletal remains will barely make the needle quiver on the ol' Horrorscope, but nearly 3000 years ago, when burial rites were something you wouldn't even deny a hated enemy, one has to assume it would have far greater implications for the listener. So that's a bit of what I went with in my sermon.

In the Midst of Life...

Media vita in morte sumus.

That is to say, “In the midst of life, we are in death.”

It’s a sentiment used as an antiphon in church singing and chants going back more than a thousand years, commonly sung during the 3rd to 5th Sundays in Lent, in fact.

It’s an easy sentiment to appreciate, because it’s true, and it’s always been true. Humans have lived under the shadow of their own mortality since pretty much the beginning of humanity, regardless of whether you are looking in the fossil record or the book of Genesis.

Beyond the fear of death, many cultures are fearful as to what happens to our remains afterwards. This is beyond any hopes or fears about life after death, which, sorry folks, I am not even getting into today!

A lot of the ancient peoples, including the Israelites, held that the proper interment of remains was vitally important. In fact, the worst thing you could promise an enemy was to leave their remains on the battlefield instead of being buried or entombed. A curse in Deuteronomy assures covenant breakers that their “corpses will become food for all the birds of the air and for the beasts of the field, with no one to frighten them off.”

The dead were usually interred quickly, within a day, unembalmed, as much for their spiritual well being as for the prevention of ritual impurity among the living.

“In the midst of life, we are in death.”

It’s true, in many ways, we are surrounded by death.

We see reports from conflict zones in Syria, Eastern Ukraine, South Sudan, and see the body counts rise horrifically.

It seems like every other week there is a terrorist attack like the one in London recently.

Even in our community, we read the papers and read about terrible crimes, of passion and dispassion alike, leaving a trail of lost lives and traumatized memories.

Worse yet, you can’t escape into television even if you avoid the news! Death is all pervasive there too. In the past you had Six Feet Under, and Dead Like Me, now you have your choice of any number of vampire soap operas, iZombie or The Walking Dead, possibly the most popular show on television right now.

Beyond literal death, we invoke un-life on a regular basis in our harried, worrisome lives.

“I didn’t get much sleep last night, I’m dead on my feet today.”

“It’s so dead in here today.”

“Poor thing, she is just dead tired.”

“He is dead-set against that guy leading the party.”

“Did you catch that flu bug going around? You look like death warmed over…”

“Stephen is just beating this point to death…”

Death is pervasive, there is no denying it; “in the midst of life, we are in death.”

Death takes center stage in our scriptures today too.

In our Gospel reading, John tells one of the most significant stories of Christ’s workings, the raising of Lazarus from the dead.

It is incredibly dramatic, you could easily imagine parts of it depicted in a movie trailer. The disciples warning Jesus to stay out of Bethany, lest he be stoned! “Lord, if you were here, my brother would not have died.” (Pack your bags, you’re goin’ on a guilt trip!) And what a shot could be made out of one of the shortest verses in the Bible: “And Jesus wept.”

You can’t show the story’s ending in the trailer, but who isn’t chilled by the thought of Jesus raising his voice and calling with a clear voice into the now open tomb, “Lazarus, come out!” And darned if the dead fella doesn’t do exactly that, still wearing the wrappings they bound him in. But before that happens, Jesus weeps, and this is important, because as we weep, God weeps with us.

In case those of a skeptical nature want to take the position that Lazarus was in fact just a heavy sleeper, or had perhaps fallen into some sort of coma, John takes special care to remind us that Lazarus has been in this cave for 4 days. Without food or water in the tomb, a sickly man would surely have perished, but more importantly, in the Jewish tradition, the body and soul part ways after three days. What Jesus has done isn’t just special, it is miraculous.

It is the high point of Jesus’s ministry in many ways, rife with allegory. It is a key moment in the Gospel narrative, as after this point those in opposition to him quickly move to have him killed. Jesus bringing the dead back amongst the living also echoes the famous passage we heard from Ezekiel.

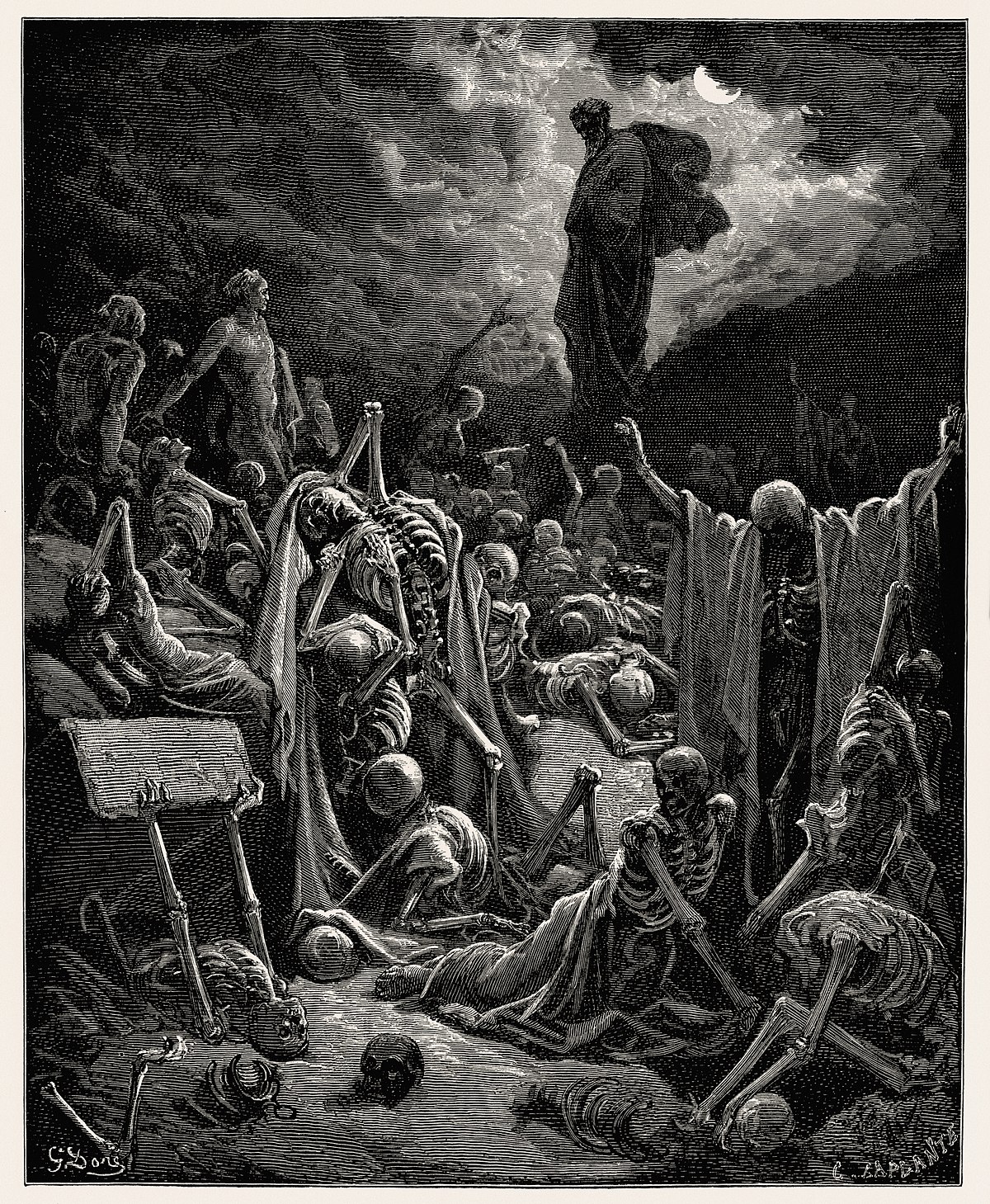

Ezekiel relates the story of his being taken in spirit by God to a valley filled with bones. Some translations call it “the” Valley of Dry Bones, imbuing it with some significance. Is there a Valley of the Moist Bones? Ick. Maybe this valley is a battlefield, maybe a bunch of cadavers just happened to end up there, who knows. What is important is just how unnatural it is.

It’s an ominous scene to us now, a valley full of bones, but imagine how it must have appeared to Ezekiel, a man who would have felt that even his enemies deserved a proper burial, and whose culture perhaps didn’t trivialize death and body parts the way ours does. I imagine it was pretty horrifying!

To make matter worse, God springs a pop quiz on our boy Zeke, asking him if the bones could live. Ezekiel, being no one’s fool, wisely hedges his bets with the scriptural equivalent of a shrug, saying, in essence, “God only knows”.

God then tells Ezekiel to prophesy to the bones, telling them that God will restore movement, and flesh and finally breath to them. Ezekiel, being a faithful servant to God, does exactly this, and is probably not surprised when things unfold just as foretold. He describes the rattling heard as the multitude of bones begin coming together, ‘bone to its bone’.

Quick sidebar: how many of you, right now, are thinking of a particular spiritual that outlines the connecting of ‘them bones, dem bones, dem dry bones’? “Ankle bone connected to the leg bone/ leg bone connected to the knee bone/ knee bone connected to the thigh bone”? Just me? No matter, but like the songs says, “now hear the word of the Lord”!

After the bones come together, and Ezekiel preaches the breath into them, God reveals that he is not creating a legion of the undead, but is merely illustrating a metaphor: “Mortal, these bones are the whole house of Israel. They say, ‘Our bones are dried up, and our hope is lost; we are cut off completely.’”

Ezekiel is then commanded to proclaim once again, this time for real, this time to tell the people of Israel, living in exile in Babylon, that God will open their graves, He will bring them out of their graves, and return them to their native soil.

He gives hope to a people in bondage.

Part of me wonders- of the two amazing things we heard from the scriptures, which is the more miraculous; the raising up of a body without life, or the instilling of hope into a people who had none?

In the end, it doesn’t matter much, as they both come from the same source, and in much the same way: a messenger delivering the will of God, the word of God, the very breath of God.

We enjoy tremendous, almost unparalleled freedoms here in 21st century North America, but we still live in bondage, bondage to fear. Fear of chaos, fear of exile, fear of change, fear of the Other, and yes, fear of death.

Worst of all, there are those who propagate these fears, not because they share them, but because there is some political or financial benefit to be wrought from our fear.

A non-binding motion condemning Islamophobia was passed in the House of Commons last week, but not unanimously, and without a lot of popular support as 42% of Canadians were opposed to it. Those opposed did so for a variety of reasons, semantics, precedent, or catering to bigotry.

As our neighbours to the south struggle to get anything done in government, and as the jibes amongst Conservative leadership candidates get more and more barbed, the level of divisiveness is almost overwhelming. It can leave a person without hope, feeling as one dead. There is a temptation to stop Lazarus on his way out of the cave and say, “You don’t wanna come out here, buddy; in fact - make room in there for one more.”

There are days when I need God’s breath to enter me, as it entered those bones that He raised up in Ezekiel’s vision.

The same breath that reanimated the house of Israel.

The breath in the voice of Jesus, commanding Lazarus to come out of the tomb.

Deep in my cave of fear, my valley of hesitancy, my tomb of loneliness, I need to feel that breath, hear that voice.

It takes a bit of bravery, like it did for Thomas when he said to the other disciples, “Let us go, that we may die with him.”

And it can be tough, but if I try, if I strain, I can hear it - no, feel it. A compulsion to remain hopeful, to maintain some kind of optimism, to have faith that I am not yet dead, and that others have felt the same stirrings.

And working together, we can accomplish God’s will, and accomplish things that might seem impossible now, but will be called miraculous later.

“In the midst of life, we are in death.” It’s still hard to refute. But what impedes us more as we try to build the world God wants for us: death, or the fear of death?

Think about it, and then consider how many times in the Bible we are told to ‘fear not’.

As the season of Easter draws near its end, with death and resurrection yet to come, let us never forget: with God as our breath, and Jesus as our teacher, we can rise again, out of despair, out of hopelessness, out of the many tombs we find ourselves in.

No comments:

Post a Comment