I had known since probably elementary school that there were indigenous carvings in the rocks in Southern Alberta. But I had no idea just how culturally significant these petroglyphs were until we visited Writing-on-Stone/Áísínaiʼpi.

The Sweetgrass Hills just over the border in Montana are a sacred place to the Blackfoot people, and they also believe that spirits inhabit the hoodoos and rock formations in the coulees of Writing-on-Stone. Because of this, not just anyone was allowed to write on the rocks - these are not just jottings or musings or recollections (although some are biographic in nature), but the products of visions, sometimes obtained under trying circumstances.

You can hike on your own to see the Battle Scene petroglyph I mentioned in my previous post, but to see the majority of the most significant carvings, you need to take a guided tour into a restricted area of the park -an archaeological preserve. At $19 a person, this is a bargain, and I heartily recommend anyone visiting the park for even a day to take advantage of it.

Thanks to COVID we couldn't take a bus down from the Visitor's Centre. Instead, we and the eight other participants formed a mini-convoy in our own vehicles and followed our interpreter, Laura, past the gate and descending down to a gravel parking area close to the Writing-on-Stone Rodeo Grounds (fun fact - Alberta singer/songwriter Corb Lund competed there in his youth).

After a short briefing on rattlesnake safety in which we were assured that no one in Alberta has ever died of a snakebite (and that there is actually more danger due to bacteria from their dirty fangs than their venom - ick), we set off. It was a short walk up some stairs to a plateau with benches facing the canyon walls, and Laura stood below the first panel, pointing out details with her walking stick.

We were lucky to have Laura - she has degrees in both archaeology and geography as I recall, but more importantly, she possesses a genuine passion and respect for indigenous culture and history which she was eager to share with us.

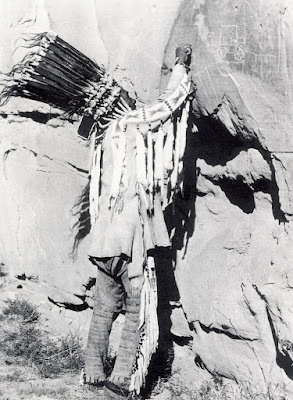

Over the next hour, she pointed out many details to us about the elements of the various panels we were viewing. A little of this I already knew, like how the horses brought here by the Spaniards predated the arrival of Europeans to the plains and had a tremendous impact on the lives of people living here in the 1700s. In some of the petroglyphs, you can see figures behind large discs which we now know are full-body shields that stretched from shoulder to ankle. These were abandoned once warriors and hunters took to riding horses instead. (Fun fact - the Blackfoot language had no word for horse, so their name for them means "elk-dog.")

These pictures do a poor job of conveying the content, but you might recognize some elements - v-necked people, a buffalo, a beaver.

Much of what we learned was new to me though, like the idea that the spiritual nature of the carvings meant that Blackfoot Medicine Men stated they could change overnight. They sought wisdom and augury from them, believing they could warn of nearby enemies or dire outcomes of battles.

Just below and to the right of the centre of the picture above is something that looks like an axe (or a hockey stick, as is often volunteered to Laura) and something that looks like a broom. Archaeologists puzzled over these until a Blackfoot elder explained that the first item was in fact a medicine pipe and the second a type of offering pole topped with feathers and stuck in the ground at a ceremony called an All-Night Smoke, variations of which are still done today.

The round impact marks are in fact bullet holes, presumably from the North West Mounted Police outpost located directly across the river. A replica of the outpost was recreated at the mouth of Police Coulee in 1975, making the view far more similar to what it had been over a century ago.

No comments:

Post a Comment